Jean-Stanislas Bareth is a first-year master student at the IEE-ULB. After a bachelor in political science at the ULB during which he was able to write for the student journal “Eyes on Europe”, he continues to deepen his knowledge of the European Union with the master in European studies.

Jean-Stanislas Bareth is a first-year master student at the IEE-ULB. After a bachelor in political science at the ULB during which he was able to write for the student journal “Eyes on Europe”, he continues to deepen his knowledge of the European Union with the master in European studies.

Thomas Rambaud is a second-year student at the IEE-ULB. After two years at the ULB in Political Science, he completed an Erasmus year in Sweden, at Uppsala. Today, as part of his Master’s degree in European Studies, he continues to write his thesis and publish articles for Eyes on Europe.

Thomas Rambaud is a second-year student at the IEE-ULB. After two years at the ULB in Political Science, he completed an Erasmus year in Sweden, at Uppsala. Today, as part of his Master’s degree in European Studies, he continues to write his thesis and publish articles for Eyes on Europe.

Following the various panels and conferences organized by the Institute of European Studies on European Solidarity (6-7 June and 5 September 2019) in the context of the Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence project, two students from our Institute interviewed Mr. Georges Dassis, former President of the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), on several themes related to European solidarity: Brexit, a review of the last EU legislature and on room for improvements for the EU.

Do you think that we can be proud of Europe today? Are we in better shape than 5 years ago?

Yes we can be proud of Europe. Europe exists, peace persists and the latter is never guaranteed a priori. Europe has made undeniable progress in terms of integration, solidarity (the foundation of this European Union) and for social matters over the past five years, even if it is insufficient.

The younger generation, yours, is fortunate to have been born in a regime of freedom of expression, of association, in democratic nations.

There is a well-being shared and guaranteed by peace. I, who was born at the beginning of the Greek Civil War (1946-1949), saw three generations who did not experience a war. This peace comes from the very existence of this European Union, formerly Europe of the six which quickly received requests for enlargement, from Greece in 1961, followed by Portugal and Spain. These association agreements had hitherto been frozen because these countries were dictatorships. The Union was already the protector of democratic freedoms.

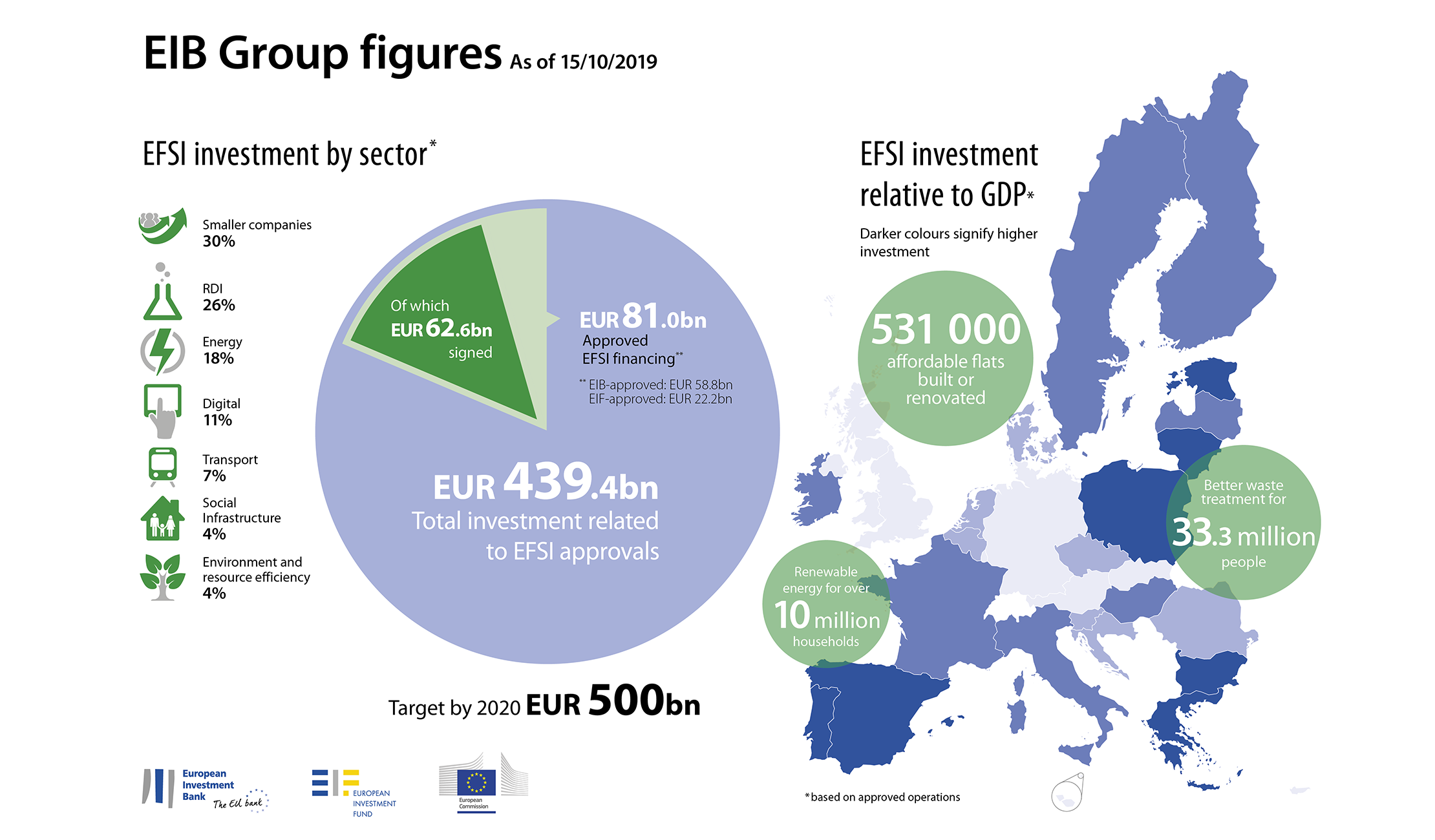

We are in better shape than we were five years ago, thanks to the Juncker Plan and especially thanks to Jean-Claude Juncker’s personality. I had the chance to work with him during my term as President of the EESC. There was a renewal because this union had principles and foundations: one of these foundations was solidarity, embodied, for example, by the European Social Fund. Its mission was to achieve “equal opportunities” between the Member States, which showed great disparities during enlargements.

So all these concrete acts of solidarity have had a real success. But in 2008 we suffered the catastrophic consequences of an ‘imported’ financial crisis. Heads of State and Government, in addition to the role of the Commission which could have been better, have largely forgotten this founding concept. Some countries that were doing well, like Germany, got rich on the back of countries in difficulty, like Greece, Ireland or Portugal. Indeed, the crisis context drew to some member States inward. Taking a specific example: it was the IMF that agreed to lend money to Greece on acceptable terms instead of the European Union. In my opinion, there is no place to think in a selfish way, we must progress and move forward together and not try to be a step ahead of others.

Fortunately, Jean-Claude Juncker arrived. At the time, I began a constructive criticism of the Juncker Plan where I pushed for higher investment. I think his plan is a success and that’s why I think we’re in better shape than five years ago.

Is Brexit the direct consequence of a lack of European solidarity?

I sided in favor of keeping the United Kingdom within the European Union. The referendum gave the result that we know. But even though I’m not a native English-speaker, I felt, during my travels in the U.K., there was a real attraction for the European project.

However, there are always those who highlight things that do not work in the EU. And people who are not experts tend to believe and listen to these criticisms as sacred words. For me, since the accession of the United Kingdom, there has never been an important decision the UK has not tried to block. It’s sad, because culturally, historically, politically, the British island is fully part of the European continent. In 2016, we wondered what would become of the British in the European institutions, and three and a half years later, they are still not sure of going out.

Looking back, we must say that the future should not be worse, but better.

Is a Social Europe one of the only effective ways to revive the European idea?

It’s a very important way, it’s not the only one and it’s not enough.

In a nutshell, I would say that the EU was basically an economic union, the social was incidental. It started to take a bigger space in the policy-making, but there is still much to be done. Having had the unanimity of the EESC members, I proposed a European minimum income. I pushed especially for a European unemployment insurance. In my opinion, if this insurance existed at the European level, we would guarantee survival to its inhabitants in their own countries. Thus one would avoid important movements of migrations. This measure would be beneficial to varying degrees in all European countries.

In the immediate future, there should be a real European defense policy.

Despite all the efforts of Federica Mogherini and all her good will, which I felt through our discussions, she did with “what’s to hand”.

What do you think of a commissioner charged with the portfolio of the European way of life? Is there a European way of life?

There has been too much noise made on this issue, in my opinion it’s awkward, because it can be interpreted in a different way. What is the European way of life? These are countries that are democratic, guarantee human rights, the rule of law, freedom of association and so on. A country, to join the EU, must fulfill these criterion, but not only a economic development criteria but it must also respect the acquis communautaire, it must respect the principles and values of the European Union. If we are interested in migrants for example, we cannot accommodate 50 million economic migrants, it is not possible, however,

we have the moral obligation, but also the legal obligation, to host the true refugees, those who flee oppression, war, death.

By leaning on the judicial side, the Member states are bound by the Geneva Convention of 1951. It allowed us to welcome the refugees of the Soviet block, and more particularly the Hungarians after 1956. It is therefore a paradox that today the Hungarian government refuses to accept any refugees and works with Turkey to keep refugees on its territory.

What advice would Georges DAssis give to young students?

First of all, we must remain optimistic, but not stupidly optimistic: we must say that nothing will ever happen on its own, we must not remain inactive. We must not think that today is more difficult than yesterday, because it is false. Yesterday and in my youth, it was worse. We must participate in civic life, we must have projects, not necessarily grandiose projects, but we must think of ourselves and of others. We must help the person who is doing worse to get better.

You also have an immense interest in making this European Union known, in criticizing it, improving it but not demolishing it.

Criticism must be constructive. We must not fall into the trap of populists, whether extreme left or far right who put on the back of Europe all that is wrong. You must not play their game and fight the fake news, to restore the truth and encourage the European Union.